Adam Sobel and I have a new paper on Potentially Extreme Population Displacement and Concentration in the Tropics Under Non-Extreme Warming.

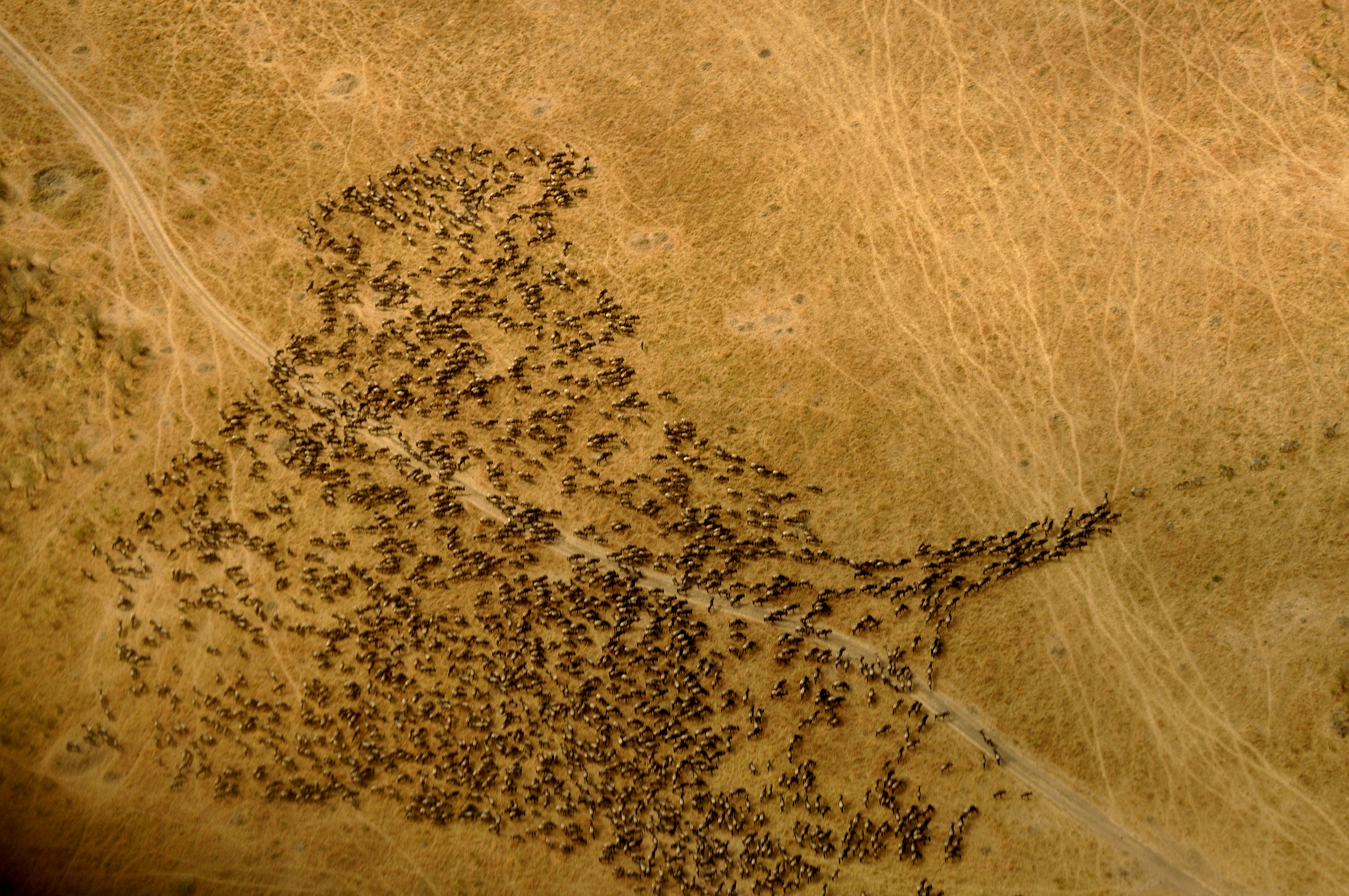

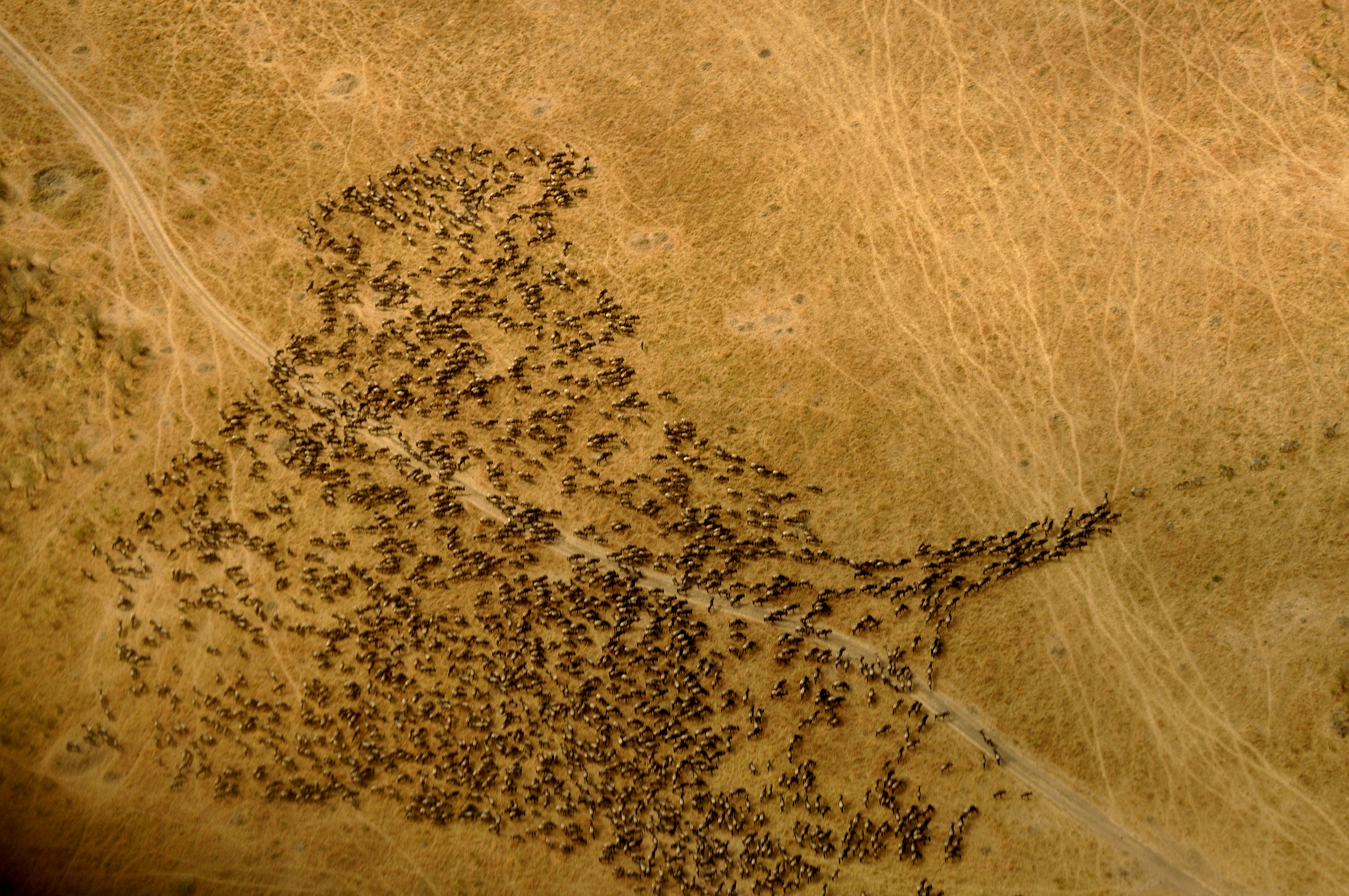

The paper is a theoretical exercise making a simple point: tropical populations that migrate to maintain their temperature will have to move much further that their counterparts in middle latitudes. This results from well established atmospheric physics that aren't focused on by the researchers who usually think about climate change and migration. One reason this result is interesting is that, in a sense, the physics of the tropical atmosphere "amplify" the impact of warming (at least in this dimension) so that even small climate changes can produce really large population displacements in the tropics (theoretically).

The paper is a theoretical exercise making a simple point: tropical populations that migrate to maintain their temperature will have to move much further that their counterparts in middle latitudes. This results from well established atmospheric physics that aren't focused on by the researchers who usually think about climate change and migration. One reason this result is interesting is that, in a sense, the physics of the tropical atmosphere "amplify" the impact of warming (at least in this dimension) so that even small climate changes can produce really large population displacements in the tropics (theoretically).

Here's the abstract:

The paper is a theoretical exercise making a simple point: tropical populations that migrate to maintain their temperature will have to move much further that their counterparts in middle latitudes. This results from well established atmospheric physics that aren't focused on by the researchers who usually think about climate change and migration. One reason this result is interesting is that, in a sense, the physics of the tropical atmosphere "amplify" the impact of warming (at least in this dimension) so that even small climate changes can produce really large population displacements in the tropics (theoretically).

The paper is a theoretical exercise making a simple point: tropical populations that migrate to maintain their temperature will have to move much further that their counterparts in middle latitudes. This results from well established atmospheric physics that aren't focused on by the researchers who usually think about climate change and migration. One reason this result is interesting is that, in a sense, the physics of the tropical atmosphere "amplify" the impact of warming (at least in this dimension) so that even small climate changes can produce really large population displacements in the tropics (theoretically).Here's the abstract:

Evidence increasingly suggests that as climate warms, some plant, animal, and human populations may move to preserve their environmental temperature. The distances they must travel to do this depends on how much cooler nearby surfaces temperatures are. Because large-scale atmospheric dynamics constrain surface temperatures to be nearly uniform near the equator, these displacements can grow to extreme distances in the tropics, even under relatively mild warming scenarios. Here we show that in order to preserve their annual mean temperatures, tropical populations must travel distances greater than 1000 km over less than a century if global mean temperature rises by 2C over the same period. The disproportionately rapid evacuation of the tropics under such a scenario causes migrants to concentrate in tropical margins and the subtropics, where population densities increase 300% or more. These results may have critical consequences for ecosystem and human wellbeing in tropical contexts where alternatives to geographic displacement are limited.